The Opioid Crisis – Where It Starts

The opioid crisis is raging with close to 80 overdose deaths every single day in USA (1). It is crazy that at least half of these deaths involve legal prescription opioids which are heavily marketed by the industry for their benefits. Physicians are urged to cut down on prescribing, but may not know how to. I believe that many of these deaths could be avoided by better communication at the time when pain is initiated or managed in the hospital, surgery suite, or on the dentist’s chair. These are the places where the trail of opioid prescriptions often starts.

A recent article in the Boston Globe describes the ordeal a patient endured who had heroically overcome prior drug use (2). Afraid of getting hooked again, he repeatedly alerted doctors to his history but nobody seemed to listen to his pleas. Over the course of a protracted postoperative recovery he ended up with prescriptions for oxycontin in amounts equivalent to 8-15 bags of heroin. A repeat procedure and its aftermath were painful and he had withdrawal symptoms attributed to infection. More pain was treated with more narcotics. The idea that prescribing large amounts of highly addictive narcotics gives the patient and doctor peace are a fallacy. Instead, a few minutes engagement at the time of the initial pain infliction in the operating room could have made all the difference.http://comforttalk.com/wp-admin/media-upload.php?

The story reminds me of an experience with uterine fibroid embolizations where a small tube is inserted via the groin arteries to block off blood flow to these benign tumors that cause excessive bleeding, pain, and the effect of a growing mass in the abdomen. Devoid of blood flow these tumors immediately start dying down which can cause more or less discomfort at the time of the procedure and afterwards. One of my colleagues wanted the procedure to be pain-free and did his cases under epidural anesthesia and heavy dosages of sedatives and narcotics. The only problem was that while his patients seemed fine in the hospital that wasn’t necessarily the case afterwards. The epidural catheter was pulled right before their discharge home and even a full prescription for narcotics didn’t do the trick. Repeat calls including nights and weekends and visits for pain management to the ER with more prescriptions were a consequence.

Based on one of our prior clinical trials, I used a regimen that not only entailed less pain, anxiety, and complications but also resulted in only half the amount of sedatives and narcotics needed (3). I encouraged my patients to communicate during the procedure, used a self-hypnotic relaxation script at the beginning, and allowed the patients to determine how many drugs they wanted to be comfortable during the procedure and afterwards. By the time they were ready to go home I had a pretty good idea how much medication they would need at home and when they could switch over to regular Tylenol for breakthrough pain. Most importantly, my patients had learned a skill of how to interact with discomfort at the time it occurred and could benefit from that later on. This Comfort Talk way of spending perhaps an extra 1-3 minutes at the beginning of a procedure that is potentially painful and checking in afterwards not only made all the difference for the patients but they felt proud about being able to help themselves. It also gave me more peace of mind and more sleep at night not having to deal with patients in distress. Thus to think that a large oxycontin prescription saves times and improves patient satisfaction is quite misplaced.

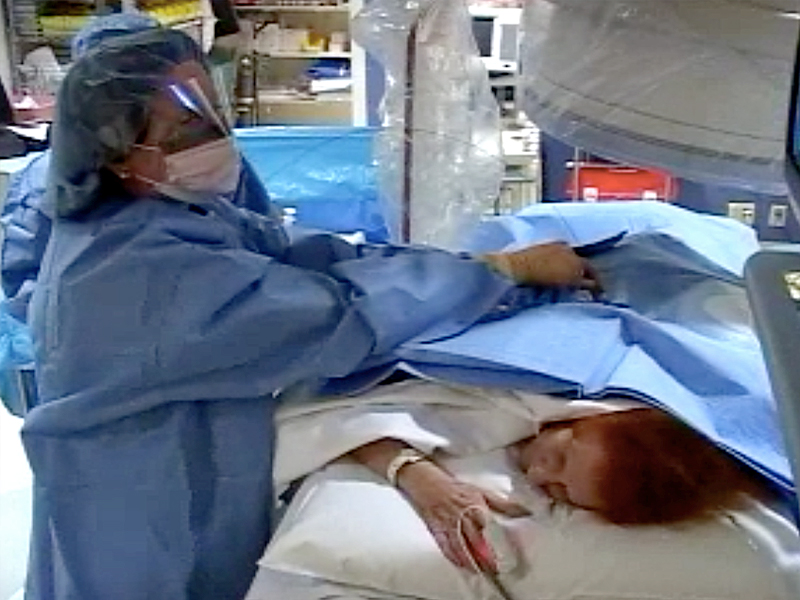

The same approach can be used for managing the kidney stones and ureter stents the patient from the Boston Globe described. The picture demonstrates me placing such a stent for a patient with a kidney stone. The Comfort Talk script was read to her while being prepared for the case e.g. without losing a second of operating room time. Another advantage of the self-hypnotic relaxation state is that the patient can talk and let the operator know when adjustments are needed for comfort – such as on the picture where I adjust the length of a stent to avoid bladder irritation.

With words it is just like with the stitch in time – “one in time saves nine.” Addressing addiction before it starts is so much easier than once a patient is full-blown in the throes of physical dependency. We all can play a decisive role in this.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention& control: Opioid overdose. Understanding the epidemic. 2016. Epub 03/14/2016. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

- Mnookin S. I have a drug history. The hospital didn’t seem to listen. Boston Globe and statnews. 9 June 2016. https://www.statnews.com/2016/06/09/opioid-prescriptions-addiction/).

- Lang EV, Benotsch EG, Fick LJ, Lutgendorf S, Berbaum ML, Berbaum KS, et al. Adjunctive non-pharmacological analgesia for invasive medical procedures: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000 Apr 29;355(9214):1486-90. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10801169